Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750)

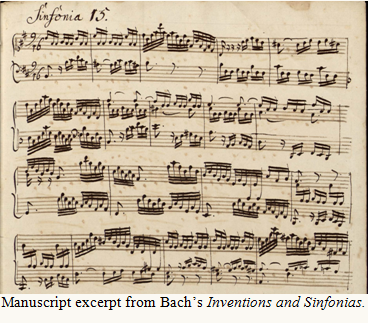

Sinfonias, BWV 787–801 (ca. 1723)

Johann Sebastian Bach spent the years between 1717 and 1723 as Kapellmeister at the court of Prince Leopold in Cöthen. Patron and employee stayed on good—even affectionate—terms throughout Bach’s tenure. (The Prince even served as godfather to one of Bach’s children, Leopold Augustus, who, sadly, did not survive his first year.) The position at Cöthen was unique for Bach (or any previous member of his musical family, for that matter) in its secular nature. Prince Leopold was a great lover of concert music, and spent nearly a quarter of his revenues on his orchestra. Naturally, the majority of Bach’s duties pertained to the orchestra, though he also spent time composing keyboard music for both his patron and himself. Many of Bach’s major instrumental works date from this period, including the Brandenburg Concertos, Violin Partitas, Cello Suites, Inventions and Sinfonias, the first volume of the Well-Tempered Clavier, and the Chromatic Fantasia and Fugue.

In addition to being purely instrumental music without liturgical motivations, many of these works were written with pedagogical aims. This is demonstrated most clearly on Bach’s own title page for the Inventions and Sinfonias:

As with the Orgelbüchlein (Little Organ Book), the Inventions and Sinfonias were composed with one particular student in mind, Bach’s eldest son Wilhelm Friedemann. The Inventions and Sinfonias are demonstrations of contrapuntal inventiveness and economy in both two and three voices respectively. Each pieces begins with a short motif that is then imitated in the subsequent voices. In true Bach fashion, however, the pieces are never merely exercises in technique; rather, they are fully realized compositions.

Cello Suite No. 1 in G major, BWV 1007 (ca. 1720)

In discussing Bach’s enduring achievement as an instrumental composer, the editors of the New Bach Reader write, “In all of [his music] he brought seeds well germinated by his predecessors to fruition on a scale undreamed of before him. And thus without any break with the past—in fact, as the great conservator of its legacies—Bach took what had been handed down to him and treated with a boldness that often seemed revolutionary.” No description could better summarize the Six Suites for Unaccompanied Cello.

Bach’s Cello Suites—along with the corresponding set of partitas for solo violin—were written at Cöthen during the same phase of Bach’s life as the previously mentioned Inventions and Sinfonias. The suites were likely composed for one or more of the talented cellists in the Cöthen court orchestra.

While Bach was by no means a cellist, he was a highly accomplished violinist, and was thus able to apply his technical expertise on the violin to the instrument’s larger cousin. There is little evidence to suggest that the Cello Suites have an explicitly pedagogical purpose like the Inventions and Sinfonias. However, like many of his Cöthen-era works, the Cello Suites demonstrate in musical form the expressive, formal, and contrapuntal possibilities of purely instrumental music.

Each of the Six Cello Suites employ the popular Baroque dance forms around which the instrumental suite developed. The core movements of any Baroque suite are the Allemande, Courante, Sarabande, and Gigue. In the First Suite in G Major, Bach adds an introductory Prelude, as well as a pair of Minuets before the Gigue finale.

In the Cello Suites, Bach writes for the essentially melodic instrument in such a way as to clearly suggest both distinctive harmonic motion and independent contrapuntal voices. Despite being much loved by a small handful of connoisseurs and virtuosos, the Cello Suites and Violin Partitas were to remain relatively unknown until their eventual publication in 1828, over a century after their composition. In the twentieth century, the Cello Suites became world famous thanks to Pablo Casals’ landmark Abbey Road recordings of the 1930’s, and Yo-Yo Ma’s Grammy Award-winning 1985 album. The opening measures of the First Suite in G Major have become one of the most recognizable melodies in all of music.

Olivier Messiaen (1908-1992)

Appel interstellaire (Interstellar Call) (1971)

from Des canyons aux étoiles… (From the Canyons to the Stars…)

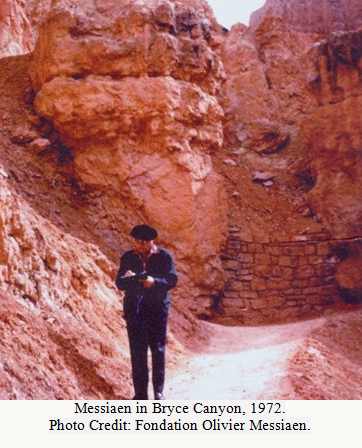

Interstellar Call, for solo horn, is the sixth movement of French composer Olivier Messiaen’s From the Canyons to the Stars…. Over 100 minutes in duration, this orchestral cycle was commissioned by the great American arts patron Alice Tully in celebration of the 200th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence.

Messiaen was at first reluctant to accept the commission. But Tully persisted and eventually persuaded the composer to accept. However, an appropriate subject matter initially eluded the composer. As Messiaen himself describes it:

“I considered the subject matter for the new score, and it struck me that writing a work for the United States implied that I like the United States, that I even love it. But how to love those skyscrapers I cannot stand? So I searched my library and found in an art book the most beautiful thing in the United States: Bryce Canyon in Utah. I said to my wife, ‘We must go to Bryce Canyon!’”

When he arrived in Bryce Canyon, Messiaen found precisely the subject that could inspire him to compose about America. He was awestruck by the sense of the divine in the “deserted and wild” landscape. During his week-long visit, Messiaen set off on day hikes “immersed in total silence,” transcribing bird songs and admiring the magnificent red-orange rock formations.

Indeed, the visit encompassed the very extramusical inspirations that were always central to Messiaen’s music. He writes further:

I wanted to compose a geological work, in tribute to the canyons. I also wanted to do a colored work. You know the importance I attach to the relationship of sound and color, and with this subject I was at home; I had red-orange rocks I was able to translate into my chords and orchestration. From the Canyons to the Stars… is another ornithological work: in it are found all the bird songs I transcribed in the United States, and particularly in Utah, along with a few other bird songs from other lands: Africa, Japan, and the Hawaiian Islands.

But I also wanted to write an astronomical work and to raise myself up from the depth of the canyons to the beauty of the stars. I was interested in astronomy in my childhood and, here, I focused on Aldeberan, one of the brightest stars in the firmament. Having left the canyons to climb to the stars, I had only to keep going in the same direction to raise myself up to God. So my work is at once geological, ornithological, astronomical, and theological. Despite the importance of color and birds, it’s above all a religious work of praise and contemplation.

But I also wanted to write an astronomical work and to raise myself up from the depth of the canyons to the beauty of the stars. I was interested in astronomy in my childhood and, here, I focused on Aldeberan, one of the brightest stars in the firmament. Having left the canyons to climb to the stars, I had only to keep going in the same direction to raise myself up to God. So my work is at once geological, ornithological, astronomical, and theological. Despite the importance of color and birds, it’s above all a religious work of praise and contemplation.

The solo horn features prominently throughout the entire work, most notably in the sixth movement soliloquy, Interstellar Call. It is once again worth quoting Messiaen at length:

The solo horn features prominently throughout the entire work, most notably in the sixth movement soliloquy, Interstellar Call. It is once again worth quoting Messiaen at length:

Two texts from the Psalms and the Book of Job inspired this piece. They are absolutely extraordinary texts. The first one says, speaking of God, ‘He heals the brokenhearted and binds up their wounds. He determines the number of the stars and gives to all of them their names.’ This text is amazing because it shows us God as both the immense and formidable creator of the whole firmament and as sympathetic to the humbler beings we are, even to the lowliest ant. The second text, from the Book of Job, is a sort of outcry against the problems that all the suffering of humanity poses for us: ‘O earth, cover not my blood, and let my cry find no resting place!’ This is a criticism and questioning of suffering; I’d add that this phrase is an extension of the preceding one, which affirmed that he who knows the number of the stars also knows the wounds of the brokenhearted. And of this piece, which sums up all the questioning about misfortune and suffering, it can be said that the entire work answers it by showing, alongside the atrocities surrounding us, the miraculous beauties of our planet and the hope of still greater beauties after death.

Despite many requests from soloists, Messiaen was in fact reluctant to detach the movement from the rest of the work. However, Interstellar Call matches closely the description given of a solo horn work Messiaen composed as part of a tombeau of memorial pieces for a Paris Conservatoire colleague who had died in 1971. And indeed, its expressive intensity and masterful bravura horn writing, made Interstellar Call’s entrance into the solo horn repertoire all but inevitable.

Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847)

Piano Trio No. 1 in D minor, Op. 49 (1839)

In the essay collection Composers on Music, editor Sam Morgenstern writes an introduction for Felix Mendelssohn so vivid and concise that it is worth quoting at length:

It is small wonder that Mendelssohn grew into one of the most cultured musicians who ever lived, coming as he did from a home of wealth and breeding, a home where the elite of the diplomatic, artistic, literary, and scientific worlds assembled—where Goethe, the sumum bonum of intellectual and social prestige, was admired. Provided with the best tutors, supplied with a private orchestra and any other facilities necessary to try out his experiments in composition, he developed into a finished pianist, composer, and conductor.

He has frequently been compared to Mozart, both of them having been Wunderkinder. But whereas Mozart combined the Italian with the German spirit, Mendelssohn’s was essentially German, not in its reactionary but in its classical aspect. His curiosity and the encouragement of his composition teacher, Zelter, led him to a profound study of Bach, whose St. Matthew Passion he resurrected from oblivion. A nationalist, he founded the Leipzig Conservatory to further German art and artists, and included in its faculty a brilliant galaxy of teachers. As conductor of the Gewandhaus orchestra in Leipzig, he elevated it into one of the most polished organizations in Europe.

Despite being one of the leading musical figures in the powerful rising tide of German Romanticism, Mendelssohn was at heart a classicist. His close study of Bach (whose cultural revival he helped mount), Mozart, and Beethoven left an inescapable mark on his work as a composer. Yet Mendelssohn was also fully steeped in the rapidly expanding harmonic language of his day. Like Bach before him, Mendelssohn sought in his own music to renew the great achievements of the past and unite them with the expressive ethos of the present.

Despite being one of the leading musical figures in the powerful rising tide of German Romanticism, Mendelssohn was at heart a classicist. His close study of Bach (whose cultural revival he helped mount), Mozart, and Beethoven left an inescapable mark on his work as a composer. Yet Mendelssohn was also fully steeped in the rapidly expanding harmonic language of his day. Like Bach before him, Mendelssohn sought in his own music to renew the great achievements of the past and unite them with the expressive ethos of the present.

This interplay between formal tradition and harmonic innovation is at the heart of the Piano Trio No. 1 in D Minor, Op. 49. The work is brooding and poetic yet always maintains a sense of formal clarity. The Piano Trio was composed initially in July of 1839. As with a number of Mendelssohn’s composition, it was then set aside before being revised and completed in September of the same year. The Piano Trio’s final version, however, may have been much more classical in style had it not been for the intervention of Mendelssohn’s friend Ferdinand Hiller. Hiller felt the piano writing was too archaic, and suggested a number of stylistic and textural changes to make the work sound and feel more modern.

Composer Robert Schumann, Mendelssohn’s friend and near-exact contemporary, described the piece as “the Master Trio of the Present.” Schumann continued saying, “Mendelssohn is the Mozart of the nineteenth century, the brightest musician, who sees the clearest through the contradictions of the present and is the first to reconcile them.” Indeed, Mendelssohn’s seemingly effortless inventiveness and lively musical textures made him in his lifetime one of the most famous and beloved composers in Europe.

Johannes Brahms (1833-1897)

Trio for Horn, Violin, and Piano, Op. 40 (1865)

In January 1865, Johannes Brahms received an urgent telegram from Hamburg. His beloved mother Christiane had suffered a stroke and was not likely to live much longer. Brahms rushed home, but did not arrive in time to be at her side when she died. After overseeing the funeral and making sure his surviving family was provided for, the devastated composer returned to Vienna.

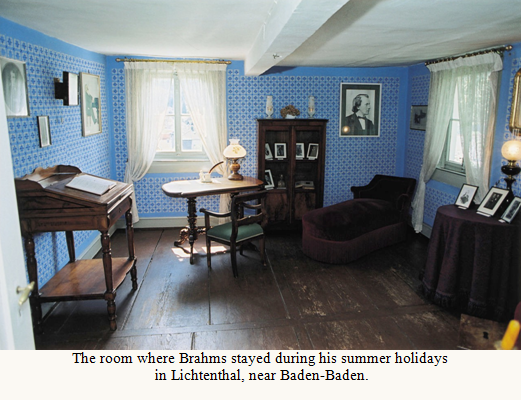

In his ensuing state of despair, Brahms found solace in his work. A cellist friend wrote of checking in on him while he was playing Bach. As Brahms told him of his loss, tears streaming, he never once stopped playing. By April, Brahms was writing to his dear friend Clara Schumann with sketches for two movements of his nascent German Requiem. However, Vienna was not providing a suitable working environment for the still grieving composer, and Brahms soon left for a long summer holiday in Lichtenthal, a mountain town near Baden-Baden.

In his ensuing state of despair, Brahms found solace in his work. A cellist friend wrote of checking in on him while he was playing Bach. As Brahms told him of his loss, tears streaming, he never once stopped playing. By April, Brahms was writing to his dear friend Clara Schumann with sketches for two movements of his nascent German Requiem. However, Vienna was not providing a suitable working environment for the still grieving composer, and Brahms soon left for a long summer holiday in Lichtenthal, a mountain town near Baden-Baden.

Brahms rented a set of rooms from a Widow Becker, and would return to this same retreat time and again in the coming years. The peaceful qualities of the mountain town naturally gave Brahms a great deal of musical inspiration. He had a steadfast routine of rising early, fixing a strong pot of coffee, and going for a hike, whilst he would plan the day’s work. After his hike, Brahms would spend some four hours composing before joining the Schumann’s—who also vacationed in Lichtenthal—for lunch and recreation.

It was in Lichtenthal that Brahms composed much of the Trio for Horn, Violin, and Piano, Op. 40. In later years Brahms would even point out the exact spot where he was hiking when the opening theme for the trio came to him. The Horn Trio is notable for its both its pastoral and elegiac qualities. The first movement eschews traditional sonata-allegro form for a more rounded and melodic song-form. Given the tragedy with which the year began, the Adagio mesto third movement can only be interpreted as a memorial for Brahms’ late mother.

Another hint to the Horn Trio’s memorial nature is found in Brahms’ decision to compose for the valveless Waldhorn, or natural horn. Brahms had strong familial associations with the Waldhorn. His father was a musician in the Hamburg orchestra and taught his young son to play the instrument as a child. By the time Brahms composed his Horn Trio, however, the Waldhorn was rapidly becoming obsolete, being replaced by the modern valve horn. However, Brahms greatly favored the more archaic instrument, with its distinctive stopped notes and expansive horn sound. Brahms exploits both these expressive qualities masterfully throughout the Horn Trio.